THE "ALWAYS RAISE" POKER RULE

WHEN AUTOMATIC DECISIONS FAIL

This article examines a single, specific idea: the always raise poker rule as it applies to pre-flop raises from late position in live, full-ring cash games.

The rule is simple.

If you choose to enter the pot from late position, you should always raise.

It is repeated so often that many players stop treating it as a decision at all.

It becomes automatic.

Late position equals raise.

Move on.

That automation has consequences.

One of the reasons late-position raises get called so frequently in live games is that everyone knows what they represent. In many cases, they are not perceived as strength raises. They are perceived as position raises. When a raise stops conveying strength, it also stops accomplishing some of the very things it is supposed to accomplish.

This matters, because raising pre-flop is not an abstract action. It is supposed to do something.

WHY IS THIS A PRE-FLOP DISCUSSION?

Before going any further, one boundary needs to be clearly stated.

This is a pre-flop discussion only.

Pre-flop and post-flop raising are fundamentally different decisions. Pre-flop, ranges are wide and uncertainty dominates. Post-flop, hands are more defined, board texture matters, and value extraction becomes a legitimate and often primary objective.

The reasons for raising pre-flop are not the same as the reasons for raising post-flop. This article deals only with the former.

THE THREE LEGITIMATE REASONS TO RAISE PRE-FLOP

TO GATHER INFORMATION

TO THIN THE FIELD

TAKING THE LEAD

A raise forces responses. Folds, calls, and reraises all narrow ranges and reveal tendencies in ways a flat call does not.

Fewer opponents mean fewer competing ranges, less equity dilution, and clearer decisions after the flop. This is especially important for hands that do not perform well in multiway pots

Raising establishes initiative. It allows you to represent strength and control the first aggressive action on later streets.

Those are the drivers.

What raising is not for, pre-flop, is simply building the pot.

The pot growing is a side effect, not a reason. If none of the three drivers above apply, increasing the size of the pot does not suddenly become meaningful on its own.

WHEN AUTOMATIC RAISES UNDERMINE THEIR OWN PURPOSE

This is where automatic late-position raises begin to work against themselves.

When everyone expects a raise from late position, the informational value drops. When calls become routine, thinning the field often fails. And when players raise pre-flop only to check the flop by default, the logic collapses entirely.

You paid extra to take the lead.

Then you immediately gave it back.

That is not a question of style. It is a contradiction in purpose.

This leads to a simple but important principle.

If you put extra chips into the pot pre-flop and cannot clearly articulate why—information, thinning, or initiative—there is a strong chance the raise was not deliberate. It may have been habitual. It may have been rule-driven. But it was not well defined.

That does not automatically make the raise wrong.

It means the decision itself was never examined.

Late position is the correct place to have this discussion because it represents the most favorable conditions for the rule to succeed. If the assumptions behind the always-raise rule begin to strain even here, that matters.

Only after the decision is clearly defined does it make sense to examine which types of hands place the most stress on those assumptions—and why.

That is where our example enters the discussion.

CHOOSING A REPRESENTATIVE EXAMPLE (WITHOUT LOSING THE POINT)

WHY THIS DECISION IS NOT UNIQUE TO POCKET PAIRS

The pre-flop decision we are examining is not exclusive to pocket pairs.

The same assumptions behind the always raise poker rule are present when players raise from late position with hands like A-K, A-Q, A-J, K-Q, or K-J. In each case, the raise is justified by position, initiative, and the expectation that those advantages will hold post-flop.

What changes from hand to hand is not the structure of the decision, but how stress shows up once the flop is dealt.

That distinction matters. It allows us to examine the thinking process without pretending that one specific holding defines the entire problem.

At the same time, analyzing every possible hand class would turn this article into a reference manual rather than an examination of decision-making. That is not the goal here.

WHY WE NEED A SINGLE, CONTROLLED EXAMPLE

To examine a decision properly, it helps to work from a controlled example rather than a broad collection of hands. The goal is not to catalog situations, but to isolate the assumptions behind the decision itself.

A useful example needs to meet three criteria. It must be common enough that players regularly face the situation. It should sit in the gray area where rules are often followed automatically. And it needs to expose the assumptions behind the raise without relying on obvious edge cases.

Pocket eights meet those criteria cleanly. They are neither a premium hand nor marginal junk. Instead, they occupy a middle ground—strong enough to invite automatic raises from late position, yet vulnerable enough that the assumptions behind those raises are frequently tested in live games.

That balance is what makes them useful.

POCKET EIGHTS AS A LENS: NOT A RULE

Pocket eights are not being used here because they are special. They are being used because they are representative.

The same thinking process we apply to pocket eights can be applied to other hands that share similar structural characteristics. What we are examining is not how to play eights, but how the decision to raise behaves when the underlying assumptions are under pressure.

By keeping the example narrow, we keep the analysis honest.

We are not trying to solve every hand.

We are trying to understand when and why a rule begins to strain.

With that framing in place, we can now move into the math that actually challenges the assumptions behind automatic late-position raises—starting with what pocket pairs face once the flop is dealt.

THE MATH THAT CHALLENGES THE "ALWAYS RAISE" RULE

Overcards Are the Default, Not the Exception

One of the quiet assumptions behind the always raise poker rule is that the raiser will frequently carry a meaningful advantage beyond the flop.

With non-premium pocket pairs, that assumption runs into a mathematical problem almost immediately.

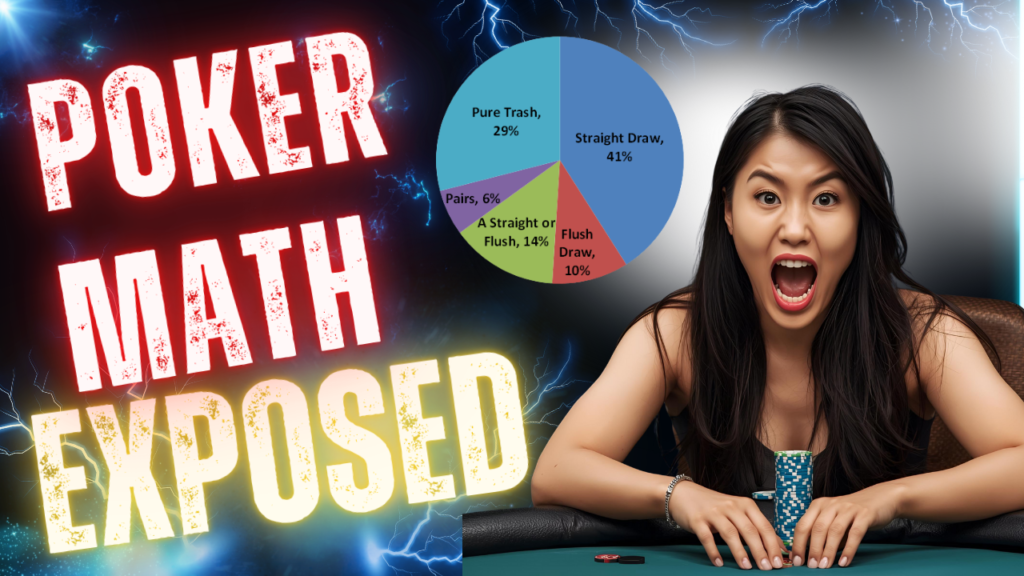

Using pocket eights as a representative example, the probability of seeing at least one overcard on the flop is approximately 85%. With pocket nines, that number is around 80%. With pocket tens, it is roughly 70%. Even with pocket jacks, an overcard appears on the flop more than half the time, at approximately 55%.

As the rank of the pocket pair decreases, the probability of overcards increases in a predictable way. This is not a marginal effect and it is not situational. It is structural.

By the river, the likelihood that one or more overcards have appeared becomes overwhelming for this entire class of hands.

This is not a judgment about pocket pairs.

It is a description of the environment they are most likely to face.

When a decision is made repeatedly under conditions that undermine its assumptions the majority of the time, that decision deserves closer examination.

IMPROVEMENT IS RARE AND BINARY

Pocket pairs do not improve along many different paths.

They do not gain relative strength simply because the board pairs.

They do not benefit from coordination in the way suited or connected hands do.

Most board developments leave their relative standing unchanged or worse once overcards appear.

Their primary meaningful improvement comes from a single event: flopping a set.

The probability of flopping a set is exactly the same for every pocket pair. It is approximately 7.5 to 1 odds, or about 11.8%.

That probability does not increase because a player raised pre-flop.

It does not change because the raise came from late position.

It does not improve because initiative was taken.

The math is indifferent to how the pot was entered.

This matters because many players intuitively expect the raise itself to “do something” for the hand. From a probability standpoint, it does not.

MULTIWAY POTS COMPRESS EQUITY

Another assumption behind automatic late-position raises is that the field will thin.

In live cash games, that assumption often fails.

When multiple players call a raise, equity compresses. Each additional range increases the likelihood that an overcard connects with someone, and it reduces the clarity of where a pocket pair stands once the flop is dealt.

Position still matters.

Initiative still exists.

But neither of them changes the underlying probabilities.

Hands whose equity depends heavily on a low-frequency improvement event feel this compression more acutely than hands with multiple ways to improve.

Again, this is not an argument for or against raising.

It is a mathematical condition that changes the shape of the decision.

WHY THE MATH COMES FIRST

The math does not tell you what to do.

It tells you what conditions you are operating under.

When overcards appear most of the time, meaningful improvement is infrequent, and equity is shared across multiple opponents, the assumptions behind the always raise poker rule deserve to be tested rather than accepted.

This is where the decision tree begins to branch.

Before asking what the best action is, it is worth asking a simpler question:

How often do the conditions required for this rule to succeed actually exist?

That question sets up the logical analysis that follows.

WHERE THE MATH BEGINS TO STRESS THE DECISION

WHEN ASSUMPTIONS AND REALITY START TO DIVERGE

ISOLATION IS ASSUMED, NOT GUARANTEED

INITIATIVE HAS A COST

The math in the previous section does not invalidate the always raise poker rule.

What it does is place conditions on it.

Raising pre-flop from late position assumes that certain things will happen often enough to justify the extra investment. The math shows that, with this class of hands, those assumptions are frequently under pressure once the flop is dealt.

This is where the decision tree begins to branch.

The purpose of this section is not to answer the decision, but to identify where the reasoning behind it becomes fragile.

One of the primary reasons to raise pre-flop is to thin the field.

The math shows why this matters. When overcards appear most of the time and improvement is infrequent, the number of opponents becomes a critical variable.

In live cash games, late-position raises often fail to isolate. Calls are common, especially when the raise is expected and perceived as positional rather than strength-based.

When isolation fails, the assumptions behind the raise are no longer fully intact. The decision now depends on how well the hand performs in a multiway environment where overcards are likely and equity is shared.

That does not make the original raise wrong.

It means the conditions have changed.

.

Another assumption behind automatic late-position raises is that taking the lead creates leverage.

Initiative does provide leverage.

But it also has a cost.

You pay extra chips pre-flop to take that lead. When overcards appear and multiple players remain, the value of initiative becomes conditional rather than automatic.

This is where the contradiction introduced earlier begins to surface. Paying to take the lead only has value if that lead can be meaningfully maintained. When initiative is taken by habit and then surrendered by default, the logic of the original decision weakens.

Again, this is not about what should be done next.

It is about whether the initial investment accomplished what it was supposed to accomplish.

INFORMATION LOSES VALUE WHEN RAISES ARE EXPECTED

POSITION HELPS, BUT IT DOES NOT SOLVE STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS

THE QUESTION THE DECISION MUST ANSWER

Raising pre-flop is often justified as a way to gather information.

That works best when responses are meaningful.

When late-position raises are automatic and widely expected, the informational value of the responses diminishes. Calls no longer narrow ranges in the same way they would against a perceived strength raise. They often reflect price acceptance rather than hand quality.

The math explains why this matters. When overcards are common and improvement is rare, decisions rely heavily on clean information. When that information becomes noisy, the decision tree becomes less stable.

Position is real.

It matters.

It provides advantages that should not be dismissed.

But position does not change the frequency of overcards.

It does not increase the probability of flopping a set.

It does not prevent equity compression in multiway pots.

What position does is allow you to see these problems more clearly. It does not eliminate them.

This is why position alone cannot carry the entire decision. It must be considered alongside the mathematical conditions the hand is most likely to face.

At this point, the issue is no longer whether raising from late position is “good” or “bad.”

The issue is whether the assumptions behind the always raise poker rule are present often enough to justify treating it as automatic.

That is the question the decision tree must answer.

The next step is to introduce the most overlooked variable in this entire discussion: opponent tendencies.

OPPONENT TENDENCIES AS A FIRST-CLASS VARIABLE

WHY TENDENCIES CANNOT BE AN AFTERTHOUGHT

PLAYERS WHO CALL "JUST TO CALL"

Up to this point, the discussion has focused on structure and math. That is intentional. Math defines the environment the decision must operate in.

But math alone does not determine how that environment behaves.

In live cash games, opponent tendencies often matter as much as the probabilities themselves. Yet they are frequently treated as background noise rather than as primary inputs into the decision.

That is a mistake.

A pre-flop raise from late position does not exist in isolation. Its effectiveness depends on how the players behind you respond, and those responses are driven far more by tendencies than by theory.

One of the most common opponent types in live poker is the player who calls raises simply because the price seems reasonable.

These players are not responding to perceived strength.

They are responding to opportunity.

Against this type of opponent, several assumptions behind the always raise poker rule weaken immediately:

- Thinning the field becomes unlikely

- Informational value drops

- Multiway pots become common

The math from earlier sections explains why this matters. When overcards are frequent and improvement is infrequent, additional callers materially change the shape of the decision.

This is not about exploiting the player.

It is about recognizing how their tendencies affect the outcome of the raise itself.

PLAYERS WHO PLAY TOO MANY HANDS

TIGHT AND PASSIVE PLAYERS

AGGRESSIVE AND PRESSURE-ORIENTED PLAYERS

YOUR OWN TENDENCIES MATTER TOO

Another common live tendency is the player who plays an excessively wide range.

These players are not deterred by late-position raises. In many cases, they expect them. Their calling behavior is often disconnected from hand quality, position, or range awareness.

When players like this are still to act, the assumption that a raise will meaningfully narrow ranges becomes fragile. The decision to raise is now interacting with ranges that remain wide even after aggression.

That interaction matters far more than the label attached to the raise.

Tight, passive players introduce a different set of considerations.

Their calls tend to be more selective. Their reraises are rare, and their folds are frequent.

Against this type of opponent, the assumptions behind a late-position raise may hold more often. Thinning the field becomes more plausible, and calls may convey more reliable information.

The key point is not that one tendency is “better” or “worse.”

It is that the same raise means different things depending on who is responding to it.

Loose-aggressive players add another layer of stress to the decision.

These players are more likely to challenge late-position raises, either through calls or reraises. They are also more willing to apply pressure after the flop.

The math does not change in these situations. Overcards are still common. Improvement is still infrequent.

What changes is how often initiative can be maintained and how costly it becomes to take it lightly.

Again, this does not answer the decision.

It clarifies the environment the decision must operate in.

Opponent tendencies do not exist in a vacuum.

Your own table image, betting patterns, and history influence how late-position raises are interpreted. A raise from a player perceived as disciplined does not carry the same meaning as a raise from a player perceived as automatic.

This feeds directly back into the earlier discussion about credibility. When raises are expected, they lose informational value. When they are selective, they regain it.

This is not a tactical point.

It is a structural one.

WHY TENDENCIES BELONG IN THE DECISION TREE

Opponent tendencies are not an adjustment layered on top of a decision that has already been made. They are part of the decision itself.

The always raise poker rule assumes neutral or cooperative responses. Live poker rarely provides those conditions consistently.

When tendencies are ignored, the decision becomes abstract.

When they are included, the decision becomes grounded in reality.

With math defining the landscape and tendencies shaping how that landscape behaves, one final variable remains: the broader table dynamics that tie everything together.

That is where we turn next.

TABLE DYNAMICS THAT RESHAPE THE DECISION

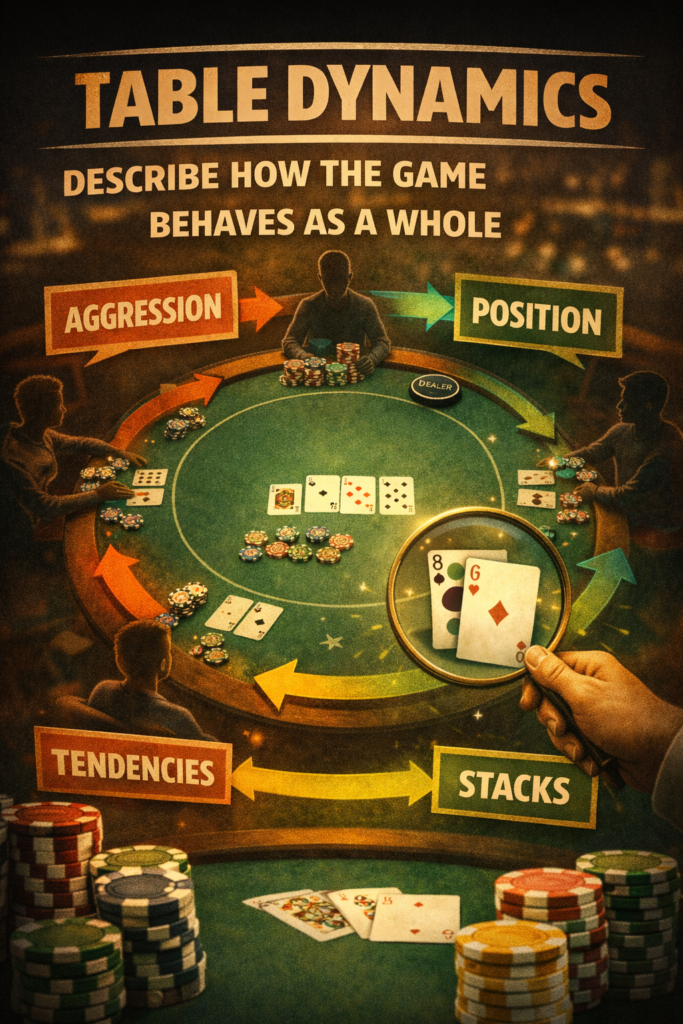

Opponent tendencies describe how individual players behave.

Table dynamics describe how the game behaves as a whole.

This distinction matters.

A late-position raise interacts not just with one opponent, but with the collective environment created by stack sizes, seat positions, and overall game texture. Ignoring those dynamics treats the decision as static when it is anything but.

The always raise poker rule assumes a relatively stable environment. Live poker rarely provides one.

STACK DEPTH CHANGES THE COST OF UNCERTAINTY

SEAT CONFIGURATION MATTERS AS MUCH AS POSITION LABELS

GAME TEXTURE SHAPES EXPECTATIONS

Stack depth is one of the most overlooked variables in pre-flop decision-making.

Deeper stacks increase the cost of uncertainty. When overcards appear frequently and improvement is infrequent, deeper effective stacks magnify the consequences of marginal post-flop situations. Shallow stacks reduce that exposure, but they also compress decision-making in different ways.

The math does not change with stack depth.

The impact of that math does.

This alters how much pressure a late-position raise can realistically apply and how costly it becomes when assumptions fail.

Late position is not a binary condition.

The number of players yet to act, their tendencies, and their stack sizes all influence how likely a raise is to accomplish its intended purpose. A raise with two tight players behind is interacting with a very different environment than the same raise with multiple loose callers yet to act.

Position provides opportunity.

Seat configuration determines whether that opportunity can be realized.

Some live games are passive and predictable. Others are volatile and aggressive. Some feature frequent limping and calling. Others see consistent three-bet pressure.

These textures are not random. They persist long enough to influence how raises are perceived and how often they succeed.

In games where late-position aggression is common and expected, the informational and thinning value of a raise declines. In tighter, more disciplined games, those same raises may carry more weight.

The rule itself does not change.

The environment it operates in does.

WHEN DYNAMICS AMPLIFY EACH OTHER

Table dynamics do not act independently.

Deep stacks combined with loose calling behavior produce different outcomes than shallow stacks combined with tight ranges. Aggressive players behind you amplify uncertainty in ways passive players do not.

Each of these factors interacts with the math introduced earlier. Overcard frequency, limited improvement paths, and equity compression do not exist in isolation. They are magnified or softened by the table as a whole.

This is why decision-making in live poker cannot rely on a single variable.

At this point, the structure of the decision is complete.

- Math defines what the hand is likely to face

- Opponent tendencies determine how others respond

- Table dynamics shape how those responses interact

None of these variables tells you what to do.

Together, they tell you what you are dealing with.

This is the difference between following a rule and evaluating a decision.

With the full framework in place, the final step is to replace rigid prescriptions with the questions that actually matter. That is where the Tools — Not Rules philosophy comes into focus.

REPLACING RULES WITH QUESTIONS

At this point, the issue is no longer whether the always raise poker rule is right or wrong.

The issue is whether it belongs in a game that is this conditional.

The math defines what non-premium hands are most likely to face.

Opponent tendencies determine how often assumptions fail.

Table dynamics shape how costly those failures become.

None of that can be captured by a single instruction.

This is where rules begin to break down—and where questions become more useful.

THE QUESTIONS THAT ACTUALLY MATTER

Instead of asking whether you are “supposed” to raise from late position, the decision becomes clearer when it is framed around questions like these:

- What is this raise supposed to accomplish here?

- Which of the three pre-flop reasons to raise actually applies?

- How likely is it that the field will thin?

- How credible will this raise be perceived by the players behind me?

- How often will overcards appear, and how many opponents will see them?

- How will stack depth and game texture magnify uncertainty?

- What happens to the value of initiative if it is taken automatically and surrendered immediately?

None of these questions tell you what to do.

They tell you what needs to be true for the raise to make sense.

WHY "ALWAYS" IS THE WRONG WORD

Rules feel safe because they remove responsibility.

Questions do the opposite.

The word always assumes stability.

Live poker is unstable by nature.

When a rule ignores math, tendencies, and dynamics, it stops being a tool and becomes a habit. Habits are easy to follow—and expensive to maintain.

That does not mean raising from late position is incorrect.

It means it should be deliberate, not automatic.

THE POINT OF THE EXERCISE

This article was never about pocket eights.

Pocket eights were simply a lens—a way to expose where assumptions are stressed and where thinking tends to stop.

The real subject is decision-making.

When you replace rigid rules with disciplined questions, you don’t need to be told what to do. You can see the decision for what it is.

That is the difference between playing by rules and playing with tools.

Poker is not solved by instructions.

It is navigated through evaluation.

When a rule makes you stop thinking, it has outlived its usefulness.

When a question forces you to slow down, it restores control.

The always raise poker rule sounds simple.

The game it operates in is not.

The goal is not to reject rules outright, but to understand when they apply—and when they don’t.

That is how thinking players stay ahead of automatic ones.