PLAYING THE HAND

THE MATH STREET BY STREET

Poker decisions are not made in isolation. They evolve from street to street, and the math that governs those decisions evolves with them.

Yet most players do not think this way. They treat hands as static objects—something they have rather than something that must be continuously re-evaluated as new information enters the hand. This disconnect between how poker actually works and how it is commonly played is where many long-term leaks originate.

This article introduces a street-by-street poker math framework designed to help players understand how probabilities, pot odds, and hand strength change from the flop, to the turn, and finally to the river. The goal is not to provide rigid rules or “correct” lines of play, but to show how the underlying math behaves as a hand develops.

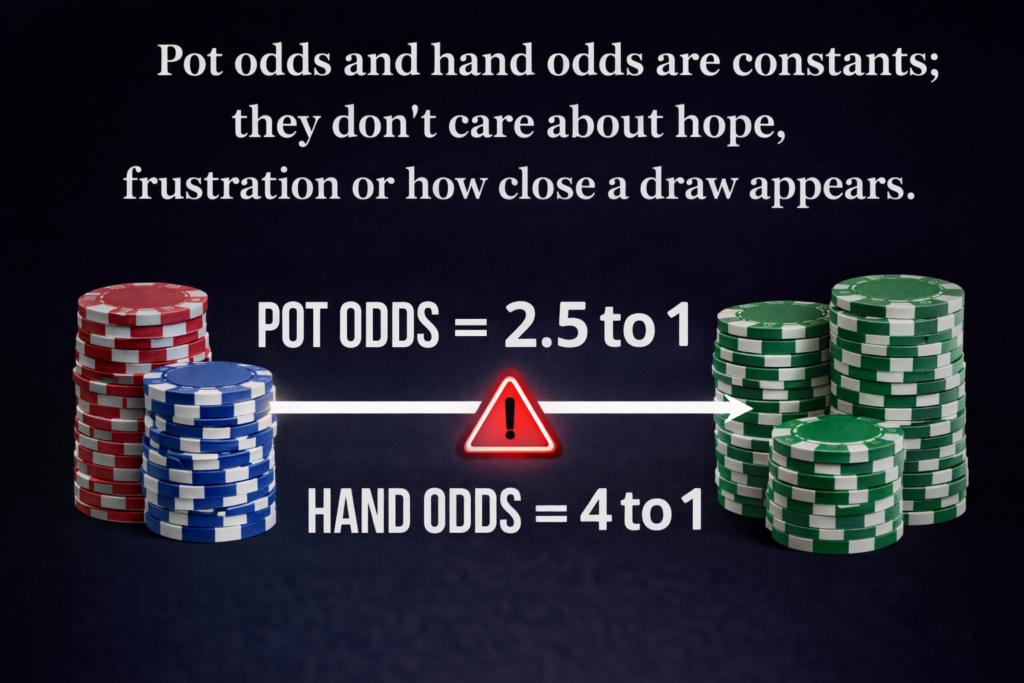

Pot odds and hand odds are constants. They do not care about hope, frustration, or how close a draw appears. What changes from street to street is the relationship between those odds and the price being offered to continue. When players fail to recognize how quickly that relationship can shift, they end up making decisions that feel reasonable in the moment but are mathematically unsound over time.

Throughout this article, the focus will remain on decision quality, not outcomes. Winning a hand does not validate a decision, and losing a hand does not automatically invalidate one. By separating results from reasoning and examining each street on its own mathematical terms, players can begin to think more clearly about when continuing makes sense—and when discipline requires letting a hand go.

This framework mirrors the Playing the Hand: The Math Street by Street video series and is intended to serve as a unified reference for understanding how poker math actually works in live, real-world play.

GUARDRAILS AND DEFINITIONS

Before examining hands street by street, it is necessary to establish clear guardrails. Without them, poker math discussions quickly become muddled by assumptions, justifications, and post-hoc reasoning that obscure what the math actually says.

This framework analyzes constant mathematical relationships, not situational outcomes.

WHAT THIS FRAMEWORK ANALYZES

This article focuses on:

- Pot odds: the price being offered to continue in a hand

- Hand odds: the probability of improving or holding the best hand

- How those two values interact as the hand progresses

These values are objective. They exist independently of the players involved, the story being told at the table, or the eventual result of the hand.

When the relationship between pot odds and hand odds no longer supports continuing, the math has already spoken—regardless of what happens next.

WHAT THIS FRAMEWORK INTENTIONALLY EXCLUDES

To preserve clarity, several commonly discussed concepts are intentionally excluded from the core analysis:

- Implied odds

Implied odds are speculative by nature. They depend on future actions, player tendencies, stack depth, and table dynamics that are unknowable at the moment a decision must be made. While they can influence judgment in real play, they do not change hand probability or current pot odds, and therefore are not part of the constant math being examined here. - Psychology tells, and reads

These factors may influence decisions in practice, but they are layered on top of math—not substitutes for it. This framework establishes the mathematical baseline first. - Outcome-based validation

Winning a pot does not retroactively make a decision correct. Losing a pot does not automatically make a decision incorrect. This article evaluates decisions based on expected value, not results.

CONSTANT MATH VS SITUATIONAL JUDGEMENT

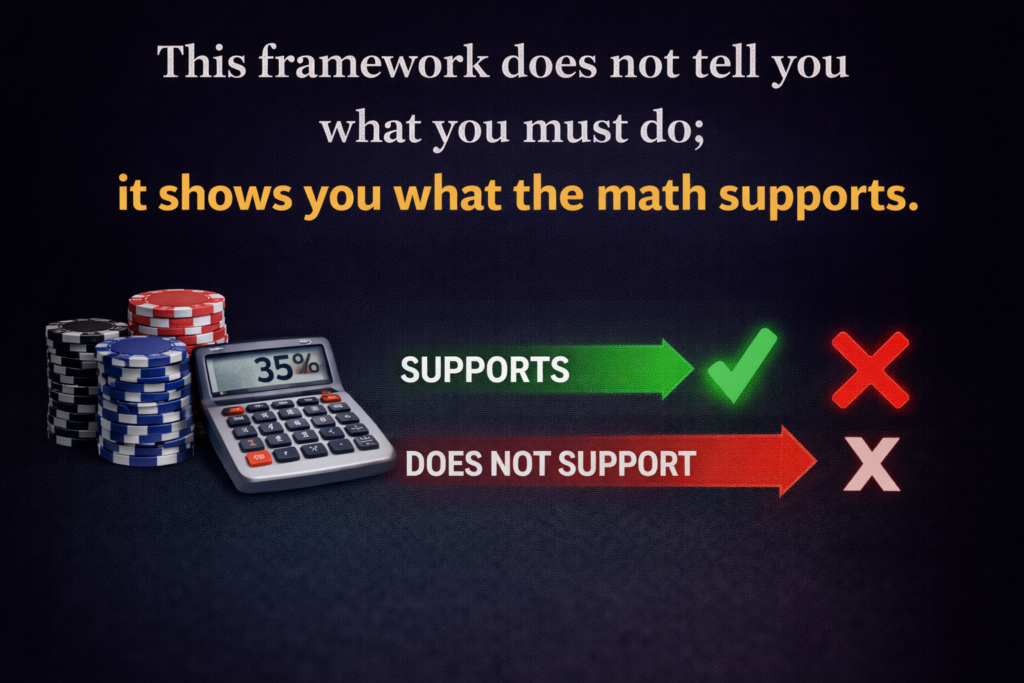

A critical distinction runs throughout this article:

- Math is constant.

- Judgment is situational.

Pot odds do not change because a player is aggressive or passive.

Hand odds do not improve because a draw “feels live.”

What does change is how a player chooses to act once the math is understood. This framework does not tell you what you must do; it shows you what the math supports. Everything beyond that point is a conscious choice.

PURPOSE OF THESE GUARDRAILS

THE STREET BY STREET FRAMEWORK

These guardrails exist for one reason: to prevent rationalization.

Most poker mistakes are not caused by ignorance of basic odds, but by the desire to justify continuing in a hand after the math has turned against it. By clearly separating constant mathematical principles from situational considerations, this framework forces decisions to be evaluated on their actual merits.

With these boundaries established, we can now examine how poker decisions truly evolve from one street to the next.

At its core, poker is a game of changing conditions. Each new street introduces additional information, alters probabilities, and reshapes the relationship between risk and reward. A street-by-street poker math approach acknowledges this reality and treats each decision as part of an evolving process rather than a standalone event.

This framework does not ask whether a hand can win. It asks whether continuing is mathematically justified at this point in the hand, given the price being offered and the probability of success.

PREFLOP: PERMISSION TO ENTER THE POT

THE FLOP: EQUITY RECOGNITION & INITIAL PRICING

THE TURN: EQUITY COLLAPSE AND DECISION COMPRESSION

THE RIVER: BINARY OUTCOMES AND SUNK-COST DISCIPLINE

The street-by-street process begins before the flop.

Preflop decisions establish the foundation for everything that follows. Entering the pot without a clear mathematical or structural reason places the player in a reactive position immediately. While preflop math is often simplified in live poker, the principle remains the same: if a hand does not have a defensible reason to be played, no amount of postflop creativity will rescue it.

Preflop mistakes are subtle, but they compound quickly.

The flop is where many players first attempt to “do the math,” but often in incomplete or misleading ways.

At this stage, the primary task is to identify what the hand actually is: a made hand, a drawing hand, or a marginal holding with limited improvement potential.

Once that classification is clear, the price being offered can be compared to the hand’s probability of success. This is where pot odds and hand odds first intersect in a meaningful way.

A call that is mathematically sound on the flop may not remain sound on the next street.

The turn is the most critical street in poker.

With one fewer card to come, drawing equity collapses sharply. Hands that were marginally viable on the flop often become mathematically unjustifiable on the turn, even when the price appears reasonable.

This is where many long-term leaks occur. Players carry forward flop logic without recalculating how the math has changed. The result is a steady accumulation of small, disciplined-looking calls that are, in fact, negative expected value.

A street-by-street poker math framework forces this recalculation to happen explicitly.

By the river, the math becomes simple but psychologically difficult.

There are no more future cards. A hand has either improved or it has not. At this point, decisions are no longer about probability, but about value, price, and the temptation to justify prior investments.

The most common river mistake is not mathematical ignorance, but emotional attachment to money already placed in the pot. Recognizing sunk costs for what they are—and refusing to let them influence decisions—is a core component of disciplined play.

WHY THIS FRAMEWORK MATTERS

Most poker errors are not dramatic. They are incremental. They occur when players fail to adjust as the math changes from street to street.

By treating each street as a fresh decision governed by constant math, this framework replaces hope and habit with clarity. It does not eliminate judgment, but it ensures that judgment is applied after the math is understood, not before.

With the framework established, we can now apply it to specific hand categories and examine how different types of hands behave as they move through the streets.

THE NO-PAIR HAND: PLAYING ACE/KING ON A MISSED FLOP

One of the most common—and most expensive—situations in poker occurs when a player raises preflop with Ace–King, misses the flop, and faces aggression in a multi-way pot.

We are playing in a $1/$3 game and raise A♠K♥ to $15. Four players call. Five players see the flop, and the pot is already $75. That number matters. In multi-way pots, someone will often connect with the board in a meaningful way.

With nine players dealt into the hand, there is roughly a 54 percent probability that at least one opponent began the hand with a pocket pair. Multi-way pots naturally favor hands that make pairs, not high-card holdings. That is the environment Ace–King is entering.

The flop comes Q♣7♦2♥. The board is dry—and it completely misses our hand.

We have:

- no pair,

- no straight draw,

- no flush draw,

- only two overcards.

Before we can reassess, the first player leads $50 into the $75 pot, making the new pot $125. All other players fold. The action is now on us.

This is where many players go wrong—not out of recklessness, but out of emotional attachment. Ace–King is treated as a “premium” hand, and players feel reluctant to release it. They convince themselves that spiking an Ace or a King justifies continuing.

WHEN PREFLOP STRENGTH COLLAPSES ON THE FLOP

But once the flop is dealt, preflop strength is irrelevant. The decision must be evaluated strictly on its current mathematical merits.

With Ace–King on this board, there are six outs: three Aces and three Kings. The probability of hitting one of those outs on the turn is approximately 6.8 to 1 against. In practical terms, this hand will miss nearly seven times for every one time it improves.

Now consider the price being offered.

We are facing a $50 bet to win a $125 pot, which gives us pot odds of 2.5 to 1.

Comparing the two:

- Hand odds: 6.8 to 1

- Pot odds: 2.5 to 1

The gap is substantial.

When hand odds are significantly worse than pot odds, continuing is mathematically unjustified. A fold here is not conservative—it is correct. Calling becomes defensible only if the bettor is capable of bluffing into multiple opponents at an unusually high frequency. In a five-way pot, a $50 lead into four players is rarely a bluff.

Even if an Ace or King appears on the turn, the hand is not automatically safe. Sets and two-pair combinations are still possible, which limits implied odds and introduces meaningful reverse implied odds. Improving does not guarantee winning the pot.

What appears frustrating at first glance is actually straightforward when evaluated properly. Ace–King offsuit, on this flop, in a multi-way pot, is simply a no-pair hand with:

- unfavorable pot odds,

- unfavorable hand odds,

- and poor future prospects.

From a street-by-street poker math perspective, the decision is clear.

The correct play is to fold and move on.

THE ONE-PAIR HAND: PLAYING POCKET NINES IN A MULTI-WAY POT

Small and medium pocket pairs are another major source of long-term losses, particularly when they are played aggressively in multi-way pots. Once again, we will walk through a real-world hand and evaluate it strictly through a street-by-street poker math lens.

We are playing in a $1/$3 game and hold 9♥9♦ in late position. We raise to $15. Four players call, sending five players to the flop with a $75 pot. As with the previous example, the number of players matters immediately.

With nine players dealt into the hand, there is approximately a 22 percent probability that at least one opponent was dealt a higher pocket pair—Tens through Aces. The more players that enter the pot, the more relevant that probability becomes when holding a hand like pocket nines.

The flop comes 10♣5♠2♠

We now have second pair to the board with no spade, no straight draw, and no meaningful redraws. The under-the-gun player checks, and the player under the gun plus one leads $40 into the $75 pot, bringing the pot to $115. Action folds to us.

Before emotion enters the decision—before the familiar thought of “but it’s a pocket pair”—the hand must be evaluated mathematically.

WHEN ONE PAIR HAS NO MATHEMATICAL FUTURE

Calling the $40 bet offers pot odds of approximately 2.9 to 1.

Now consider the hand odds.

With pocket nines, there are exactly two outs remaining in the deck. The probability of hitting one of those outs on the turn is roughly 22 to 1 against. Out of 47 unseen cards, only two improve our hand. That means we will miss the turn approximately 96 percent of the time.

Comparing the numbers:

- Hand odds: 22 to 1

- Pot odds: 2.9 to 1

These figures are nowhere close.

From a purely mathematical standpoint, continuing is a losing play nearly every time.

And the situation deteriorates further.

Even if the bettor is holding a hand such as Ace-anything of spades or a weaker spade draw that we technically beat on the flop, the next bet is almost certainly coming. On a board with two spades, an Ace, King, Queen, Jack, any spade, and several other cards all become credible and profitable barrels for an aggressive opponent.

This is not a call to “see one card.”

It is a call into a turn landscape where most cards are bad, and the few that help appear only about 4.3 percent of the time.

Even the best-case scenario carries risk. If the miracle Nine arrives—and especially if it is the Nine of Spades, one of the two remaining nines—the board now contains three spades, introducing serious vulnerability despite making a set.

Pocket pairs feel strong, but they play weak in multi-way pots because they improve infrequently, and the cards that do not improve them frequently strengthen an opponent’s story or range.

Will there be times when the best hand is folded in this spot?

Yes—and that is unavoidable.

But players who refuse to fold second pair in mathematically losing situations do not gain long-term value. They become players who occasionally fold winners but consistently pay off losing hands. That profile defines long-term losing poker.

From a street-by-street poker math perspective, the conclusion is unambiguous.The mathematically correct play is to fold.

.

THE TWO-PAIR HAND: PLAYING KIING/EIGHT ON THE BUTTOM

Two-pair hands often create more problems than they solve, particularly when they originate from weak, dominated holdings in multi-way pots. This example illustrates why hands that look powerful on the flop can become extremely difficult—and expensive—to navigate on later streets.

We are on the button holding K♦8♠. We limp in, along with five other players, and go six ways to the flop. The pot is $18.

The flop comes the A♥ K♣ 8♥.

We have flopped two pair, a result that occurs roughly 2 percent of the time. While this appears strong at first glance, this is exactly the type of situation created by playing “face-card anything”—hands that connect just enough to create difficult decisions, but lack structural strength.

Yes, we are likely ahead at the moment. But there are important limitations.

We have only four outs to improve to a full house—two Kings and two Eights—and we must navigate two remaining streets. The only advantage we hold is position.

At this point, it is critical to evaluate what this hand actually beats.

On this board, we do not beat:

- Ace–King

- Ace–Eight

- any set

- any two-pair combination containing an Ace

In a six-way pot, these hands potentially exist.

.

The under-the-gun player leads $15 into the $18 pot. Three players call before the action reaches us. The pot is now $78, giving us pot odds of 5.2 to 1.

With four outs, our odds of improving to a full house on the turn are approximately 10.75 to 1 against, or about 8.5 percent. From a pure drawing standpoint, calling to improve is mathematically incorrect.

However, for the moment, we hold a made hand and are likely ahead. Given position and the modest bet size, calling is reasonable. We call.

The pot is now $93.

The turn is the Q♦, completing a possible straight.

WHEN TWO PAIR LOSES ITS STRUCTURAL ADVANTAGE

The under-the-gun player fires $65 into the $93 pot. One player calls, and the action returns to us. The pot is now $223.

Our odds of improving on the river remain approximately 10.5 to 1 against, while the pot is offering 3.43 to 1. Calling to hit a full house is clearly incorrect from a mathematical perspective, however we do have a made hand. We call, making the pot $288.

At this point, continuing with the made hand depends entirely on factors beyond raw pot odds:

- board texture,

- opponent tendencies,

- and how often these players barrel with weak one-pair holdings.

Heads-up, two pair wins roughly 80 percent of the time. Three-way, depending on player tendencies, that number often falls into the 50–70 percent range—and sometimes lower.

The river comes, the Two of Hearts, completing the potential heart flush.

The under-the-gun player bets again, this time $200 into the $288 pot. The other active player folds. The pot is now $488, and the decision is back on us.

We still have a made hand.

But, we have not improved.

The board has grown more dangerous on every street.

And the bettor has fired into multiple opponents on the flop, turn, and river.

This is the point where discipline matters.

ANALYZING THE RIVER DECISION

By the river, the under-the-gun player has taken a strong and consistent line:

- a lead into a six-way pot on the flop,

- a second barrel on the turn into multiple opponents,

- and a large river bet of $200 into $288.

This is not a weak or probing line. It represents real strength in a multi-way hand.

Before defaulting to “I flopped two pair, I have to call,” the decision must be reduced to what actually matters.

Hands We Beat

The number of hands we beat is extremely small:

- one-pair hands,

- Queen–Eight,

- Queen–Two.

That is a narrow range.

Hands That Beat Us

The list of hands that beat us is both longer and far more realistic:

- Ace–King

- Ace–Eight

- Ace–Queen

- Ace–Two

- any set

- Jack–Ten (straight)

- any heart flush

These are not fringe holdings. These are hands that commonly bet all three streets on this board texture, especially in a multi-way pot.

We beat perhaps three plausible hands.

We lose to seven or more strong, credible holdings.

THE MATH ONLY CONCLUSION

Even before factoring in player tendencies or physical tells, the math paints a clear picture.

This is a made hand with:

- very few value hands it beats,

- many realistic hands ahead of it,

- and a betting line that consistently signals strength.

This illustrates one of the core problems with hands like K-8, Q-7, J-5, K-9 offsuit, and the entire “face-card anything” category.

They create strong-looking flops with:

- limited improvement potential,

- no clean path forward,

- and growing vulnerability as the pot expands.

By the river:

- You have invested $85,

- it now costs $200 more to continue,

- and you are paying significantly more than your total investment just to confirm what the betting line already indicates.

From a street-by-street poker math perspective, the correct decision is clear.

Fold and move on.

THE SET HAND

FLOPPING MIDDLE SET ON A DANGEROUS BOARD

Sets are premium holdings, but on dynamic boards—especially in multi-way pots—they are not hands to slow-play. This example shows why strong made hands still require disciplined sizing and street-by-street pressure to deny equity and charge draws.

We hold 9♥9♦ in under-the-gun plus one. A late-position player raises to $20 preflop, four players call, and there is $100 in the pot heading to the flop.

The flop comes A♦10♠9♠ in a five-way pot.

We have flopped middle set on one of the most dangerous board textures in poker:

- the top card is an Ace,

- Ten and Nine introduce multiple straight possibilities,

- two spades create a front-door flush draw,

- and the pot is multi-way, with five players seeing the flop.

This is a strong hand, but it is not a slow-play spot. In a five-way pot on this texture, it is reasonable to expect at least some portion of the field to hold real equity.

A practical question on the flop is simple: where are we right now?

In this situation, the range of opponents’ likely holdings often includes:

- at least one Ace-x hand,

- at least one flush draw,

- a broadway straight draw such as King–Queen or King–Jack,

- and occasionally a combo draw such as Queen–Jack or seven-eight of spades that carries both straight and flush potential.

Set-over-set (Tens or Aces) is possible, but uncommon. Most of the time, pocket nines will be ahead, but surrounded by hands that can improve.

The under-the-gun player checks, and the action is on us. Our objectives are straightforward:

- Charge draws heavily.

- Thin the field.

- Build a pot that reflects the strength of the hand.

We bet $80 into the $100 pot.

That size matters because it pressures equity immediately and changes the math for every caller.

FLOP PRICING AND POT ODDS

OUR MPROVEMENT POTENTIAL

- The first caller is calling $80 to win the $180 in the pot before their call, which is 2.25 to 1 pot odds.

- If that player calls, the second caller is calling $80 to win $260, which is 3.25 to 1.

- A third caller would be getting roughly 4.25 to 1, but in most live games, three flat-calls against an $80 bet on this board is less common.

The core point is simple: the first callers are often being offered pot odds that do not justify continuing with ordinary draws. That is exactly what we want when we hold the best hand: larger pot, worse calls.

There is a meaningful exception. A monster combo draw such as Queen–Jack of spades or Seven–Eight of spades can have both straight, flush, and straight-flush equity, often totaling 15 outs, or roughly 2.13 to 1 to hit on the turn. Those hands are rare, but they do exist. The goal is not to eliminate them; the goal is to force the widest possible set of opponents into mathematically unfavorable calls.

Even while likely ahead, we can still improve.

On the flop, we have seven outs to make a full house or quads on the turn:

- three remaining Tens,

- three remaining Aces,

- and one remaining Nine.

Seven outs is approximately 5.71 to 1 against improving on the next card.

If we miss on the turn, the story does not end. After the turn is dealt, we have ten outs to a full house on the river:

- three Tens,

- three Aces,

- one Nine,

- plus three cards that can pair the turn card.

Ten outs is approximately 3.6 to 1 against.

This matters because as drawing hands fail to improve on the turn, their equity typically declines, while our chances of improving to a full house increase.

TURN ACTION AND REPRICING

We receive two callers, and with our $80 bet included, the pot is now $340.

The turn comes the 3♦.

This is an excellent card for our hand:

- it does not complete the flush, or straight,

- and it does not materially change the top-pair situation.

If opponents were on flush draws, straight draws, or combo draws, their probabilities worsened on the turn. Our set remains strong, and our full-house outs increase from seven to ten.

With $340 in the pot, we bet $220 on the turn.

This sizing accomplishes multiple goals simultaneously:

It maintains maximum pressure on draws, and forces top-pair hands to make real decisions. We are also building the pot with our strong hand, and denying cheap equity in a spot where our hand is still likely the best.

Turn Pot Odds Offered

- The first caller is calling $220 to win the $560 in the pot before their call, which is approximately 2.54 to 1.

- If that player calls, the second caller is calling $220 to win $780, approximately 3.54 to 1.

In both cases, unless an opponent holds a specific monster combo draw, continuing is often mathematically incorrect. Their equity has declined since the flop, while our hand has remained strong and retains meaningful improvement potential.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

The lesson from this hand is not merely “bet your sets.” It is more precise:

In multi-way pots on dynamic boards, strong hands must be played with sizing that:

- recognizes how many opponents are involved,

- accounts for how much equity draws truly have,

- acknowledges your own improvement potential to a full house,

- and forces opponents into mathematically unfavorable calls on every street.

This is how sets win large pots over time—not by trapping, but by charging.

After the $220 bet on the turn, both remaining players fold.

The hand ends there.

That outcome is not incidental, and it does not diminish the value of the line taken. In fact, it reinforces the entire objective of playing strong made hands correctly on dangerous boards.

By betting aggressively on both the flop and the turn:

- we forced drawing hands to make mathematically incorrect calls or fold,

- we denied cheap equity on a board rich with potential,

- and we protected our hand without needing to “get lucky” on the river.

This is an important point that often goes unrecognized.

Winning a pot without seeing a river card is not a failure. It is the expected result of correct pressure applied at the right time.

Had we been called on the turn and seen a river card, the decision would once again be evaluated independently, based on:

- the final board texture,

- remaining opponent ranges,

- and the price being offered.

But the absence of a river decision here does not indicate a missed opportunity. It indicates that the math did its job earlier in the hand.

Strong hands do not need to be disguised to be profitable. On boards like this, they need to be priced correctly.

FLUSH DRAWS AND COMBO DRAWS

WHY POSITION AND PRICE MATTER

Flush draws are among the most misunderstood hands in poker. Many players treat them as automatic continues, regardless of position, pot size, or price. This example shows why that approach quietly leaks money—and why flush draws must be evaluated street by street, just like any other hand.

We will examine the same hand in two different positions to show how price and position alter the decision, even when the cards do not change.

FLUSH DRAW FROM EARLY POSITION

We are under the gun plus one holding A♥7♥. A late-position player raises to $15. The button calls, the small blind and big blind call, and we call. Five players see the flop, and the pot is $75.

The flop comes 9♥10♠5♥ .

We have flopped a flush draw.

The small blind checks, and the big blind leads $45 into the $75 pot, making the pot $120. It costs us $45 to continue.

That gives us pot odds of 2.66 to 1.

Now consider the hand odds. A flush draw has nine outs, which puts the odds of hitting on the turn at approximately 4.22 to 1 against on the turn, and roughly the same on the river.

Comparing the two:

- Hand odds: 4.22 to 1

- Pot odds: 2.66 to 1

These numbers do not align.

From a purely mathematical standpoint, this is a fold.

The larger lesson here is structural. When hands like Ace–Seven suited are played from early position and go multi-way, they frequently place the player in situations where they must either overpay to continue or surrender equity. This is why early position requires hands with clarity. Ace–Seven suited does not offer that clarity.

THE SAME HAND IN LATE POSITION

WHEN THE MATH CHANGES

Now we take the exact same hand, A♥7♥—but this time we are on the button.

Under the gun plus one raises to $15. The same players call, and once again we go five ways to the flop with $75 in the pot.

The flop is the: 9♥10♠5♥.

Under the gun, plus one bets $45 into the $75 pot. Two players call before the action reaches us.

Now the pot is $210, and it costs us $45 to call.

That gives us pot odds of 4.66 to 1.

Our hand odds remain 4.22 to 1 against hitting the flush on the turn.

This time, the math works in our favor.

Because the pot odds are greater than our hand odds, this is a long-term profitable call. We call, and the pot becomes $255..

The turn card is the 10♦, pairing the board.

Under the gun plus one bets again, this time $155 into the $255 pot, swelling the pot to $410. Action folds around to us.

We are now being offered pot odds of approximately 2.64 to 1 to call.

Our flush draw still has nine outs, but the odds of hitting on the river are now roughly 4.11 to 1 against.

Even on price alone, this is a fold.

And the situation is worse than the numbers suggest.

The board is now paired, which introduces reverse implied odds. If under the gun plus one is firing hard into a multi-way pot on both the flop and the turn, he frequently holds a made hand—top pair, two pair, trips, or occasionally a full house.

That means even if the flush arrives, it may no longer be good.

At this point, we are not only calling with incorrect odds—we are calling in a spot where improving does not guarantee winning.

KEY TAKEAWAY

This example highlights the essence of street-by-street poker math.

On the flop:

- we had the right price,

- we had position,

- and the math justified continuing.

On the turn:

- the price worsened,

- the board became more dangerous,

- and the math turned against us.

The correct line is clear.

Call the flop when the math supports it.

Fold the turn when the math no longer does.

That is one-street poker, executed correctly.

COMBO DRAWS: WHEN THE MATH FINALLY TURNS THE TABLES

Combo draws represent one of the few situations in poker where a player without a made hand can apply maximum pressure for mathematically sound reasons. Unlike single draws, combo draws shift the equity balance and simplify future decisions by placing the player on the favorable side of probability.

This is not gambling. This is math.

PLAYING THE HAND

We are playing in a $1/$3 game on the button, holding J♥10♥.

A solid player in middle position raises to $15. Two players call, and we call behind. The blinds fold. Four players see the flop, and there is approximately $65 in the pot.

The flop comes Q♥, K♠,7♥.

This is a true combo draw:

- an open-ended straight draw,

- a flush draw,

- and multiple clean paths to winning the hand.

Some players will incorrectly describe this as a “17-out hand,” counting nine hearts and eight straight cards. That is not accurate. Two cards—the A♥ and the 9♥—complete both the straight and the flush and can only be counted once.

The correct count is 15 outs.

UNDERSTANDING THE EQUITY

FLOP ACTION & POT ODDS

EQUITY AGAINST MADE HANDS

With 15 outs:

- the probability of completing the hand on the turn is approximately 32 percent, or 2.13 to 1,

- if the turn is missed, the probability of completing by the river rises to roughly 33 percent, or 2.07 to 1,

- combined, the probability of completing by the river is approximately 54 percent, or 0.85 to 1 in our favor.

This is not a speculative call.

This is a mathematical advantage.

The preflop raiser bets $55 into the $65 pot. One player calls, bringing the pot to $175. Action is on us.

We are being offered pot odds of approximately 3.18 to 1.

At this point, the distinction between combo draws and single draws becomes critical.

If we call, we are committing to future decisions. Because of our equity, we will often have the correct price to continue on later streets regardless of bet size.

If we raise—especially in a multi-way pot—we apply maximum pressure, frequently force folds, and often eliminate difficult future decisions altogether.

Even in the worst reasonable scenario—being called by a set—the math remains favorable.

A set on the flop has:

- seven outs to improve on the turn, or 5.71 to 1 against,

- if it misses the turn, ten outs to improve on the river, roughly 38 percent, or 3.6 to 1 against.

Our combo draw, with 15 outs, has approximately 54 percent equity to complete by the river.

That equity advantage explains why experienced players will often move all-in with hands like this. Not because they are reckless, but because doing so:

- maximizes fold equity,

- simplifies future decisions,

- and places the money in the pot when the math is working in their favor.

Combo draws are powerful because they offer multiple paths to victory while reducing uncertainty. They allow players to apply pressure without relying on hope or speculation.

This is one of the rare situations where a non-made hand can legitimately drive the action.

And once again, the guiding principle remains unchanged:

One street.

One card.

One decision.

STRAIGHT DRAWS

HOW GAP STRUCTURE CHANGES THE MATH

To compare straight-draw behavior accurately, we need a consistent frame of reference. Rather than jumping immediately into board textures, we begin by defining the four straight-draw categories and selecting specific hands to represent each one.

These hands are chosen intentionally—not because every hand in the category behaves identically, but because they isolate the effect of gap structure as cleanly as possible. Each represents the most efficient version of its category. If these hands struggle, weaker versions perform even worse.

THE FOUR STRAIGHT DRAW CATEGORIES

CONNECTORS (JACK/tEN)

ONE-GAP HANDS (JACK/NINE)

TWO-GAP HANDS (JACK/EIGHT)

THREE-GAP HANDS (JACK/SEVEN)

Jack–Ten serves as the baseline for straight-draw analysis. It sits near the center of the straight spectrum and offers the highest straight-draw density of any connected hand.

From preflop to river, Jack–Ten completes a straight approximately 9 percent of the time, or about 10 to 1. No connected hand performs better. Every other category will be evaluated relative to how Jack–Ten’s equity behaves across the streets.

Jack–Nine represents the strongest one-gap configuration.

Removing a single rank immediately reduces the number of straight pathways from four to three. That loss is meaningful and often underestimated. These hands frequently feel similar to connectors, but once the math is examined street by street, they perform significantly worse.

This is where many players begin to overvalue straight draws.

With two missing ranks, straight potential drops sharply. Jack–Eight has only two straight pathways, and those paths are narrower.

This category is where players most often convince themselves they are “priced in,” despite the math consistently pointing in the opposite direction. The hand looks playable, but its straight equity is fragile.

Jack–Seven has only one possible straight pathway. There is virtually no margin for error. Chasing straights with hands like this becomes expensive very quickly.

This category is not about finding clever ways to continue. It is about recognizing that discipline—not creativity—is the correct response.

With the categories established, we now play the hands street by street and allow the math to dictate the decision points.

PLAYING THE HAND: CONNECTORS - JACK/TEN

We are holding J♠10♥ in the hijack.

There is a $15 preflop raise and three callers, including us. Four players see the flop, and the pot is $60.

The flop comes Q♦9♣3♠.

We have flopped an open-ended straight draw. Any King or Eight completes the straight, giving us eight outs.

The original raiser bets $30. One player folds, and two players call. Before the action reaches us, the pot is $150. It costs us $30 to continue, offering 5 to 1 pot odds.

With eight outs, the odds of hitting the straight on the turn are approximately 4.88 to 1 against. Because the pot odds exceed our hand odds, calling is mathematically correct. We call, and the pot becomes $180.

.

The turn is the A♣. Our draw remains unchanged. The original raiser now bets $120 into the $180 pot. Everyone else folds.

Before we act, the pot is $300. It costs us $120 to call, giving us 2.5 to 1 pot odds.

With eight outs, the odds of hitting on the river are approximately 4.75 to 1 against. The price is no longer sufficient. From a mathematical standpoint, this is a clear fold.

Nothing about our hand changed.

Nothing about our outs changed.

The price changed.

This is where many players go wrong. They feel committed because they already called once, because they are “close,” or because they only need one card. None of that alters the math.

Even strong straight draws can flip from profitable to unprofitable in a single street.

HAND NO. 2: ONE-GAP (JACK/NINE)

Now we examine J♠9♥, the strongest one-gap configuration.

From preflop to river, J♠9♥ completes a straight about 7 percent of the time, or roughly 13.29 to 1. That reduction in probability, versus connectories, matters.

The preflop action is identical: a $15 raise and three callers. Four players see the flop, and the pot is $60.

The flop comes K♦8♣3♠

We have paired the Eight, giving us three cards to a straight (Eight, Nine, Jack). However, we do not have a traditional straight draw.

To complete a straight, we must hit perfect, perfect—a Ten and a Queen in either order across the turn and river. This is a runner-runner requirement.

The original raiser bets $45 into the $60 pot. Two players call, and one folds. The pot is now $190. It costs us $45 to continue, offering 4.33 to 1 pot odds.

The probability of completing a runner-runner straight is roughly 4 percent, or about 22.5 to 1 against.

The gap between price and probability is enormous. This is not close. From a mathematical standpoint, this is a clear fold.

TWO AND THREE-GAP HANDS: WHERE THE MATH FAILS

Beyond one-gap hands, straight-draw math does not merely weaken—it fails.

The strongest two-gap hand, such as Jack–Eight, completes a straight about 6 percent of the time, or roughly 15.7 to 1.

The strongest three-gap hand, such as Jack–Seven, completes a straight roughly 5 percent of the time, or 19 to 1.

These numbers answer the question before the flop is ever dealt.

From a straight-draw perspective, these hands do not meet the mathematical threshold required to enter the pot. There is no street-by-street process to follow because the process ends preflop with a fold.

Position does not fix this. Seeing a cheap flop does not fix this. You are paying now for a result that almost never arrives—and when it does, it is often dominated.

IMPORTANT CLARIFICATION

Some two-gap hands, such as Ace–Jack or King–Ten, are occasionally playable in late position—not because of their straight potential, but because of their high-card value.

Even then, these hands remain marginal and are frequently dominated.

From a straight-draw perspective, however, they still fail the math.

Conflating high-card play with straight-draw justification is one of the most common leaks in live poker

WHAT THE MATH SHOWS

The pattern is clear.

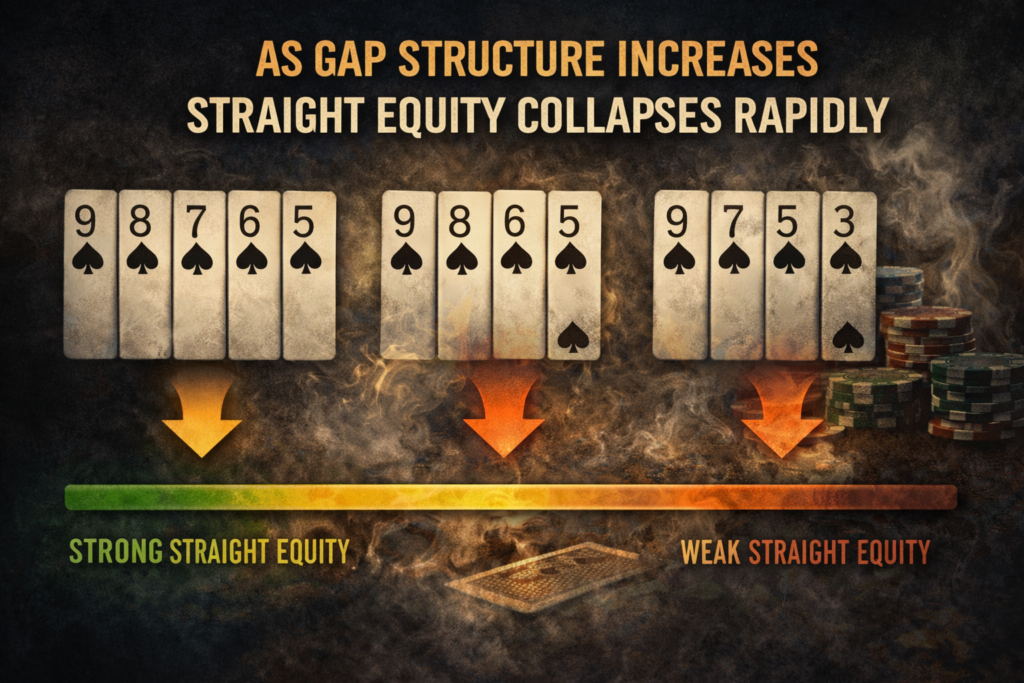

As gap structure increases, straight equity collapses rapidly:

- connectors offer the most structural support, yet still often flip from correct to incorrect within one street,

- one-gap hands look playable longer than they should,

- two- and three-gappers fail outright.

The precise percentages matter less than the direction of the math.

Every added gap:

- removes straight combinations,

- lowers probability,

- and shortens the window where continuing can ever be justified.

This is why so many players feel “close” while steadily losing money chasing straights. The structure of the hand does not support the story they are telling themselves.

Straight draws are not equal.

Gap structure matters.

Pot odds and hand odds are constants.

They do not care about hope, curiosity, or sunk cost.

Strong players are not the ones who chase the most.

They are the ones who recognize when the math has already spoken—and act accordingly.

WHAT THE MATH REVEALS (A SYNTHESIS OF THE HANDS)

By the time each hand reached its critical decision point, the pattern was already visible.

Across no-pair hands, one-pair hands, sets, two pair, flush draws, combo draws, and straight draws, the same forces were at work—only the timing differed.

The most important observation is this: equity does not decay evenly across hand types.

Some hands lose value immediately. Others hold briefly, then collapse. A small number gain strength as the hand develops. But in every case, the turning point occurred when price and probability diverged.

That divergence most often appears on the turn.

The turn compresses decisions. One card is removed. Future equity shrinks. Bet sizes increase. What looked viable on the flop frequently becomes indefensible one street later. This is not a coincidence—it is the mathematical structure of the game.

Another pattern is structural similarity. Despite different cards and outcomes, the same mistakes appeared repeatedly:

- continuing after the price worsened,

- anchoring to earlier decisions,

- confusing closeness with correctness,

- and staying in hands because of prior investment rather than present justification.

APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK IN LIVE POKER

Street-by-street poker math is not a script. It is a baseline.

The math answers a narrow but critical question:

Is continuing justified at this price, with this probability, right now?

That question must be answered before situational factors are considered—not after.

Live poker introduces variables that math alone cannot measure: player tendencies, table dynamics, stack depth, physical behavior, and recent history. These factors matter, but they come after the math establishes whether continuing is even defensible.

Using math as a crutch—calling because the odds are “close,” or folding automatically because they are not—misses the point. The purpose of the framework is not to replace judgment, but to discipline it.

Guessing before knowing the math is backwards.

Rationalizing after ignoring it is worse.

When applied correctly, the framework simplifies live decisions. It narrows the range of reasonable actions and eliminates those that are mathematically unsound. What remains is judgment, applied within defined boundaries.

This is why the approach is best described as tools, not rules.

The math does not tell you what to do.

It tells you what you are allowed to justify.

CONCLUSION: THINKING IN DECISIONS - NOT OUTCOMES

Poker rewards decisions, not results.

Every hand in this framework demonstrated the same truth: the quality of a decision is determined at the moment it is made, not by what happens afterward. Outcomes fluctuate. Math does not.

Street-by-street thinking shifts focus away from being right and toward being disciplined. It replaces emotional momentum with recalculation. It reduces volatility not by avoiding risk, but by avoiding unjustified risk.

Players who struggle are often not reckless. They are persistent. Often, they stay one street too long. They chase equity that no longer exists. They pay prices that no longer make sense.

Strong players do the opposite.

They exit earlier, when the math turns.

They let go of hands that still look promising, because it’s mathematically correct.

Not because they lack creativity—but because they understand that consistency beats imagination over time.

Pot odds and hand odds are constants.

They do not remember past streets.

They do not reward hope.

Thinking in decisions rather than outcomes changes everything.

That is the purpose of this framework.

This is the essence of street-by-street poker math — recalculating on every decision point, letting price dictate action, and exiting hands early when the numbers no longer support continuation.