HOW GTO MADE PLAYERS WORSE

A TACTICAL AUTOPSY

GTO made players worse by turning poker’s holy grail—Game Theory Optimal strategy—into a rigid, often misapplied dogma that stifles adaptability. Once hailed as the path to unexploitable play, GTO promised a future where math ruled, and instinct, psychology, and situational awareness took a backseat.

And for a while, it worked.

Until it didn’t.

Today, GTO made players worse, especially in live cash games, by fostering predictable, robotic play—rigid bet sizing, solver-driven decisions, and blind adherence to theory that crumbles in chaotic, human-driven environments.

This article is a tactical autopsy of how the GTO boom created as many problems as it solved. We’ll explore the mechanical flaws, real-world failures, and psychological traps GTO introduces—especially when misunderstood, misapplied, or followed with religious fervor.

We’ll also explain why GTO has become the SAT of poker—a standardized, rigid system that rewards memorization over creative, adaptive thinking. And we’ll offer an alternative: a strategic path forward rooted in math, observation, psychology, and real-world practicality.

THE RISE OF GTO: A GAME-CHANGER THAT CHANGED TOO MUCH

When Game Theory Optimal (GTO) strategy burst onto the scene, it was hailed as poker’s holy grail, but GTO made players worse by turning elegant math into a rigid ideology. Based on the Nash Equilibrium, GTO aimed to create a perfectly balanced strategy where no player could exploit another—because every decision was unexploitable. If both players played GTO flawlessly, neither would win or lose over the long run. But that was never the point. The real draw was this: if you played closer to GTO than your opponents, you could extract maximum value from their mistakes while remaining immune to exploitation.

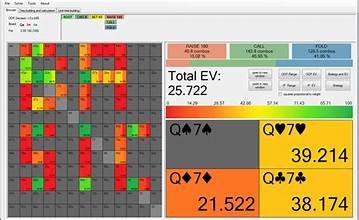

This elegant, almost poetic concept gained traction fast—especially among elite online players and math-savvy theorists. The arrival of solvers like PioSOLVER, GTO+, and MonkerSolver gave players tools to simulate hundreds of thousands of poker scenarios and generate theoretically optimal decisions for every street, every board texture, every stack size.

The promise was intoxicating: no more guesswork. No more “feel” plays. No more relying on instinct or psychology or live reads. Just plug in the variables, study the output, and memorize the lines. Poker, solved.

And for a while, it worked—in its proper domain.

.

GTO WAS DESIGNED FOR A CONTROLLED ENVIRONMENT

Here’s what most casual players don’t know: GTO was developed for heads-up play—one-on-one, controlled conditions, balanced ranges, and short-handed formats like 4-max and 6-max, especially online. That’s where the math shone. But GTO made players worse when its fever spread to full-ring live cash games, where it didn’t belong.

Imagine building a Formula 1 race car engineered for the pristine, banked turns of Monaco… and then driving it into a demolition derby. That’s what happened when GTO entered the live cash arena.

Suddenly, a tool designed for precision balance in sterile conditions was used in chaotic, unpredictable, deeply human environments—where people limp with 9-3 offsuit, talk during hands, act out of turn, and care more about ego than equity.

And yet, many players—especially newer ones—treated GTO not as a tool, but as a rulebook. An ideology. A complete replacement for strategy, context, and judgment. The result? GTO made players worse by creating a generation who raised, c-bet, and triple-barreled because the solver said to—not because the table demanded it.

FROM SOLUTION TO SYNDROME: HOW GTO MADE PLAYERS WORSE

GTO made players worse by turning a revolutionary solution into a syndrome—a rigid framework that fosters predictable, inflexible play, countering the adaptability it once promised.

When GTO was first introduced, it was heralded as a leap forward in poker evolution. But like many innovations, what started as a solution quickly became a syndrome.

What went wrong?

The answer lies not in the math—but in how the math was misunderstood, misapplied, and memorized without context.

YOU MEMORIZED THE ANSWER KEY: BUT THE TEST CHANGED

Let’s start with a powerful analogy: the SAT.

Over the last 20 years, SAT math and critical thinking scores have declined across the board【source: College Board, 2022 Annual Report】. In response, many test prep companies shifted from teaching reasoning to teaching answer keys. Rote memorization replaced adaptive thinking. Students practiced templates, patterns, and multiple-choice traps—not problem-solving.

Poker followed the same path, and GTO made players worse by encouraging this shift.

Solvers don’t produce decisions. They produce lines—a set of preferred actions based on rigid assumptions: balanced ranges, static opponents, no deviations from optimal play. But the moment those conditions don’t hold—and they rarely do—the “solution” collapses.

And yet, players cling to the outputs like gospel:

- “Solver says bluff this river 28% of the time.”

But your opponent never folds. Ever.

• “Solver says raise A5 suited under the gun in a balanced range.”

But this table has five calling stations and a maniac behind you.

You memorized the answer key—but the test changed.

Worse, the culture around GTO reinforced this rigid approach. Deviating from solver outputs became taboo. If you raised based on a read or checked because you sensed fear—you weren’t playing “correctly.”

And so began the great regression—from principles → to patterns → to parroting.

Optional Sidebar: How the SAT Is Like a Poker Solver

SAT Prep | GTO Solver Study |

Memorize formulas | Memorize solver lines |

Follow multiple-choice tricks | Follow preset frequencies |

Discourages deviation | Discourages adaptation |

Gives illusion of mastery | Gives illusion of strategy |

In both cases: “Success” means giving the expected answer—not the best one. | |

Poker isn’t a test—it’s a conversation. | |

It requires listening, adapting, and making judgment calls in real time. |

INSIDE THE WRECKAGE: A TACTICAL AUTOPSY OF GTO'S FAILURES

Even with all its theoretical brilliance, GTO made players worse in real-world poker. Why? Because GTO isn’t built for live conditions. What follows is a tactical autopsy—eight key places where solver-driven thinking collapses at the table.

THE BLUFFING PROBLEM

THE "NEVER LIMP" PROBLEM

The Mistake:

Solvers prescribe bluffing at balanced frequencies to remain unexploitable. But live poker isn’t theory—it’s people. And many of them don’t fold.

Let’s say you’re on the river, holding a busted flush draw. The solver says bluff. The pot is $200, and it recommends a $100 bet. That means you’re risking $100 to win $200—you need it to work just 33% of the time to break even.

Here’s the trap: it doesn’t work 33% of the time against calling stations. Or ego-driven players. Or bored retirees with a pair of sevens. If it only gets through 25% of the time, you’re lighting money on fire.

Even worse, solver-trained players often fail to adjust. They bluff because they “should”—not because it’s smart. GTO has no button for “this guy never folds.” But you do.

Key Takeaway:

The problem isn’t that bluffing is wrong—it’s that solvers ignore human tendencies. You can’t balance your way past a player who doesn’t believe in folding. GTO made players worse by teaching them to bluff in situations where real-world fold equity doesn’t exist.

The Mistake:

Solvers hate limping. They treat it as weak, passive, and mathematically suboptimal—and in theory, they’re right. In solverland, aggression wins.

But in real poker? Limping is everywhere.

You’re in a $1/$3 live cash game. Five players limp ahead of you. You’re on the button with pocket eights. GTO says raise—but is that wise?

Let’s break it down:

- In a 9-handed game, there’s a 26% probability that someone holds a higher pocket pair than your eights.

- There’s also an 85% chance an overcard (9, T, J, Q, K, or A) hits the flop—putting your hand in purgatory.

- And if you raise to $25 and get reraised by UTG holding pocket kings? You’ve just reopened the betting for the entire table. Congratulations—you walked into a trap.

Sometimes, the right move is to overlimp, see a cheap flop, and let the hand develop. Or trap with monsters in games where raises don’t fold out anyone anyway.

Key takeaway

Limping isn’t always weak. In games with frequent limpers and sticky callers, refusing to adjust can be far worse. GTO made players worse by forcing aggression in situations where passivity—or deception—is mathematically superior.

THE CONTINUATION BET FAILURE

THE RAISING ISSUE

The Mistake:

GTO loves the continuation bet. On the solver screen, it’s pure poetry—bet small, deny equity, balance your ranges. But in live, multiway pots? It’s a trap.

Let’s set the scene:

You raise to $15 in a $1/$3 game with Ace-Jack offsuit. Two callers behind. The big blind comes along. Four players see a flop:

9♠ 7♠ 4♥

It checks to you. GTO says, “Fire a small c-bet”—but pause.

You missed the board. And you’re outnumbered. These aren’t solver-villains. These are real-world players—some holding pocket pairs, others chasing draws they’ll never fold.

Before you fire, ask yourself a simple question: What can I beat?

In this case—nothing.

You think three people called your preflop raise and not one of them connected? It’s possible. But unlikely. To believe Ace-high is good here is a mistake born from wishful thinking.

And if you’re betting to “find out where you’re at”? You’re not betting—you’re donating. That’s not strategy. That’s impatience disguised as logic. And it’s one of the most common leaks in live play.

You bet $20. One caller. Then the button raises to $65.

You’ve just bloated a pot with air, against ranges that were strong preflop and got stronger postflop. Now what?

GTO doesn’t adjust for game texture. It assumes everyone plays ranges correctly. But live players over-call, under-fold, and trap. When three or more players take a flop, someone usually connects.

Key Takeaway:

In live games, continuation bets into multiple opponents with marginal hands are often burning money. GTO made players worse by ignoring multiway dynamics and teaching players to fire without thinking. In real poker, thinking beats theory.

.

The Mistake:

GTO solvers recommend opening wide from every position—including early. That might work in heads-up or 6-max online play, but in a 9-handed full-ring live game? It’s a recipe for disaster.

Let’s say you’re UTG in a $2/$5 game. You look down at A♣ 2♣. The solver says, “Suited wheel aces are fine—open it.” So you raise to $20.

Fold. Fold. Call. Call. Button calls. Big blind calls.

Five players to the flop.

The board comes: Q♠ 9♥ 7♦.

You’ve got ace-high and zero board coverage. You’re out of position, with no plan, and half the table is in the hand. What now?

This is where solvers get you in trouble.

They assume:

- Opponents are folding the bottom 70% of their range

- No one over-calls light

- You have post-flop fold equity

- You’ll play perfectly after the flop

But live games don’t work that way.

People call with anything suited, any pair, and any two Broadway cards. That UTG raise with A♣ 2♣? It just built a big pot out of position with no equity. And worse—you announced strength, so bluffing later is nearly impossible.

The same goes for K♠ 9♠, Q♦ T♦, and other weak speculative opens GTO allows from early position. Sure, they’re “+EV” in theory—against a solver. But live games aren’t theory. They’re messy, multiway, and full of sticky callers.

Even worse?

These raises get flattened by strong ranges behind you—pocket pairs, suited Broadways, better aces. When you do hit your kicker or a pair, you’re usually second best.

Key Takeaway:

GTO made players worse by convincing them to open hands from early position that don’t hold up in live dynamics. In a real 9-handed game, fold equity is minimal, post-flop play is tricky, and the punishment for speculative opens is high. Instead of opening “because theory says so,” open with hands that can withstand heat and play cleanly postflop.

THE ROBOT EFFECT

THE MULTIWAY DISCONNECT

The Mistake:

GTO training creates pattern players—players who make the “correct” move regardless of context. Fold this combo. Bluff this river. Size this bet. Follow the chart.

In a vacuum, that sounds solid. In the real world? It creates predictable, robotic play—and that’s a problem.

You’ve probably seen it:

- The player who always c-bets the flop, then checks the turn.

- The player who triple barrels only on Ace-high boards.

- Or the one who folds the same combos at the same time, over and over again.

They think they’re unexploitable. But in reality?

They’re fully reverse-engineerable.

Once you’ve watched them for an hour, you know exactly what they’re doing—and when.

There’s no table image manipulation.

No leveling.

No misdirection.

And no deception.

They’re running software lines at a human table.

Even elite players, after enough GTO exposure, start looking the same. They fade into the crowd. You can’t tell the difference between a pro and a training site clone anymore. And that’s not just boring—it’s beatable.

Key Takeaway:

GTO made players worse by encouraging mechanical, pattern-based poker. Great players don’t follow charts—they create controlled unpredictability. They blend balance with adaptation. They understand that poker isn’t about perfect play—it’s about getting paid. And if your opponent always knows what’s coming, you won’t be.

The Mistake:

GTO theory was originally designed for heads-up play. It expanded to 3-handed, then 6-max. But in full-ring live cash games—especially with 4 to 6 players seeing every flop—it breaks down fast.

Why? Because solvers assume a world that doesn’t exist.

They assume one villain, as well as perfect ranges.

They assume fold equity that isn’t there.

But you’re in a $1/$3 game on a Friday night. Five players just called your raise with trash. There’s no ICM pressure. No precise ranges. Just loose calls, mystery hands—and a bloated pot full of landmines.

Now what?

Your solver tells you to barrel.

To represent a strong range.

Or to bluff certain combos.

To mix in some check-raises.

But it never asks:

“What happens when three people call again?”

GTO doesn’t model that.

It doesn’t model a turn card that changes nothing—and still doesn’t scare anyone.

It doesn’t model the guy on your right who just doesn’t fold top pair. Ever.

Solvers don’t account for chaos.

And real-world poker?

It’s built on it.

Key Takeaway:

GTO made players worse by giving them a framework that falls apart in multiway pots. Real poker isn’t one-on-one—it’s often one-on-five. If your strategy can’t handle that, you’re playing the wrong game.

THE META ILLUSION

The Mistake:

GTO players love to talk about balance.

They obsess over frequencies, bet sizing trees, and range protection.

And they believe—fervently—that their opponent is thinking on the same level.

Here’s the problem:

Their opponent is just trying to see a turn.

You’re playing $1/$2 at the local card room.

Villain limp-called with Queen/Nine offsuit.

They’re not worried that your triple-barreled range is unbalanced.

They’re not considering your polarized sizing strategy.

Most likely, they are wondering if the Queen on the board is good—and how much it costs to find out.

You’re not in a leveling war.

You’re not playing Magnus Carlsen.

That’s Ray from Accounting, sitting across from you, who just got off work, called with second pair, and is thinking about whether or not he’s hungry.

And yet GTO players level themselves into oblivion:

- “If I bluff here, it balances my value range…”

- “He knows I know he’s capped, so I should raise…”

- “This line is unexploitable…”

Stop.

None of that matters if your opponent isn’t thinking in levels.

You can’t outmaneuver someone who isn’t even in the maze.

Key Takeaway:

GTO made players worse by convincing them that everyone else is playing 5D poker. They’re not. You don’t need to be balanced. You need to be better. Exploit weakness. Punish predictability. And never assume your opponent is seeing the game like you are.

THE EXPLOIT FOLD: THE MOST PROFITABLE BUTTON IN POKER

GTO players fear folding. Why? Because folding too often makes you “exploitable.” That’s solver-speak for giving up equity. But here’s the problem: most players aren’t exploiting you. They’re value betting—and that’s it.

Solvers assume your opponents are bluffing at the “correct” frequency. But when the population is under-bluffing, and you call anyway to “balance” your range, guess what?

You’re not balancing.

You’re bleeding.

In real poker, especially live games, folding is often the most +EV play available. And it doesn’t require a solver to figure that out—it requires observation, pattern recognition, and ego control.

You’re not playing defense against a machine. You’re playing offense against humans.

And most humans are not bluffing you off top pair with air.

🧠 Key Takeaway:

If the villain isn’t bluffing often enough, folding is the exploit—and it prints money.

So go ahead. Click the fold button.

It might be the smartest decision you make all night.

GTO is a powerful tool—but it’s not a religion. The best players use it as a reference, not a rulebook. Real poker is messy, dynamic, and human.

Solvers don’t tilt. Humans do. That’s where the money is.

REAL POKER IS ABOUT ADAPTATION

GTO is a compass—but poker is a map you have to draw in real time. If you follow GTO blindly, you’re just walking north, no matter what terrain you’re on. Real poker demands more than that. It requires adaptation—to the game, the players, the moment.

The best players don’t just know the math—they adjust their play on the fly. They spot calling stations and value bet them relentlessly. The better players slow down against nitty regs who only raise with monsters. They trap the maniacs. They take mental notes on every show of emotion, every chip grab, every comment—and they use it.

The better players know when to go small, when to go big, and when to check behind—not because the solver says so, but because they see the game unfolding in real time. They exploit weakness and punish imbalance.

The tools are still there—pot odds, SPR, blockers, combos—but those are just part of the picture. The rest is human. A live read. A strange line. A gut feel based on hours of play. Poker isn’t just about being correct—it’s about being better than the player across from you, right now.

In the real game, math matters. But so does psychology.

“GTO is a compass. But poker is a map you have to draw in real time.”

GTO TOOLS: USE THEM-DON'T WORSHIP THEM

Solvers aren’t the enemy. But they’re not the answer either. They’re tools—nothing more. You shouldn’t bring GTO to the felt like it’s gospel.

The best players study solvers to learn principles, not memorize charts. They don’t copy outputs—they try to understand why a line is preferred. Is it range advantage? Nut advantage? SPR pressure? Once you get that, you can start using GTO the right way: as a training tool, not a script.

Solvers are for review. Not for real-time reaction. You run hands after the session to see what you missed. You study spots off-table to sharpen your instincts. But when you’re in a live hand with two fish, a reg, and a maniac—good luck applying the perfect equilibrium strategy.

Balance matters. But only when it needs to. Against attentive opponents? Sure. Against the average $1/$3 crowd? Probably not.

GTO is brilliant theory. But poker is practical. If you treat GTO like it’s a religion, you’ll miss the whole point.

CONCLUSION

GTO isn’t the villain. It’s a powerful framework—when used correctly. But when misunderstood or blindly applied, it turns sharp players into stiff, robotic imitators.

We’ve seen the dangers:

- Overreliance on solver lines that ignore human tendencies

- Opening too wide, bluffing too much, c-betting into disaster

- Neglecting table dynamics, psychology, and exploitative edge

Rigid thinking creates brittle players. And solvers, for all their brilliance, don’t teach you how to read a room, how to spot weakness in real time, or how to adjust on the fly.

If GTO is perfect poker… why are you still losing?

The best players aren’t solver disciples. They’re independent thinkers. They study theory—but play the player. They use tools—but don’t worship them.

So take the lessons. Ditch the dogma. Learn real poker.

Because in the end, it’s not about being unexploitable.

It’s about knowing when to exploit.